Wheatus - Celebrating the 25th anniversary of the band's self-titled debut album

Wheatus: 25 Years of Alt-Rock Legacy

It’s been 25 years since Wheatus burst onto the scene with their self-titled debut album—a lo-fi, genre-blending record that gave us one of the most enduring alt-rock anthems of the early 2000s: Teenage Dirtbag. Recorded in a basement, powered by raw emotion and DIY ingenuity, the album captured a moment in time that still resonates with fans across generations. With a massive 18 date UK and Ireland tour scheduled for November and December, Wheatus are taking the opportunity to truly celebrate this wonderful milestone by playing their debut album in full. We catch up with frontman and guitarist Brendan B Brown as he makes his way through New York. As you would expect, we are given the warmest of welcomes. We’ve come loaded with questions and the great thing is that Brendan has all the time in the world for us. A sink hole has opened up on Sawmill River Parkway which means he’s going nowhere! We simply make ourselves comfortable and our conversation begins…

Well, amazingly it’s been 25 years since Wheatus’ self titled debut album was released. As someone who bought that album back in 2000, when I hear this milestone I just can’t believe that it’s been a quarter of a century. How does it feel for you? Does it feel that long?

No. It’s an interesting question because sometimes I experience the time as a vast chasm, you know, forgotten travel and lots of hours recording music and rehearsing and things like that. Sometimes I think about it and it’s like ‘if there is somebody who is 25 years old, that’s their entire life!’ When I’d been alive for 25 years I didn’t feel that long and I’m twice that now at 51. I think our brains protect us from understanding the true meaning of time.

We’re grateful for that!

I’m enjoying the delusion! (Laughs!) I think there were many years where it felt like we were going to survive, and that the tour that we were on was the last one, and having come out of that and into a new place, it’s simultaneously satisfying and unfamiliar. So it feels in that regard very new and exciting in a way that it never did when we started. This current time feels much better than the one when Teenage Dirtbag was first a hit.

Well let’s go back to that time and focus on the album as a whole because how it all came together is such an incredible story. First of all, Wheatus had already been a band since 1995. Why did it take you 5 years before you had your first album? What was happening in that time?

Well for the first 2 1/2 or 3 years I’d say I was alone in the project with a drum machine, a microphone and a bass, and I was demoing and re-demoing songs from albums 1, 2 and sometimes 3 – and even 4 and 5 - to get to a point where I understood what my voice was in the context of the music. When you make a record, a producer’s job is to shape the song to support the local, typically on a pop recording and assuming it’s not avant-garde or experimental. That’s the general goal, and I had ideas about that were way far afield. For example, the acoustic guitar being used to play metal sounds, the hybrid of hip-hop influence in the lower end of the band at the same time that the more 70s rock and 80s metal tones were coming through on the upper frequencies of the band. And also the songwriter influences from James Taylor and Paul Simon to Fugazi. If I had of gone into a studio and said “Hey, a hybrid of like, you know, LL Cool J and Metallica and James Taylor” they would’ve laughed at me in the 90s and sent me home! (Laughs!) So what I had to do was craft that production aesthetic myself. I had been in and out of enough studios and in enough projects to know that trying to convince somebody who did it on a daily basis was a dead end. So I came up with the methodology myself over the course of those 2 1/2 or 3 years, but alone recording and re-recording the songs and just trying to figure out how they could be shaped, and then I bumped into Phil Jimenez who became the co-producer and really my musical partner. On that first record we combined forces and we combined our gear because he had been amassing a bit of a ‘project studio’, as had I. So we put all our stuff in one room together and almost had a professional studio between the two of us. So we started working on these concepts for what became the third and then final draft in most cases. And the final draft was at my mother’s house in February and March of the year 2000 and that was the record that became the album. But it went through many revisions from ‘95 through to 2000 when we made that final version. So the better part of those 5 years was in the laboratory.

Well let’s pick up on how you recorded the album because you made reference there to how you almost had a professional studio. I also love the fact that you recorded the album in your mum’s basement with a control room in the dining room. You produced the record yourselves but from this lo-fi set up the album actually sounds incredible from a production perspective. No one would ever have known that it wasn’t recorded in a high-end studio. Why did you decide to take this route? Was it out of necessity, and also how easy was it to set everything up to get the sound you wanted?

All of the above! An improv approach to gear and an improv approach to setting up. If we needed a little bit of a slap echo delay, we pulled the curtain back on the bathtub in my mother’s bathroom and shut the door, or we took the rugs out so that it was little bit more reflective, and we did the acoustic guitars with me sitting on the bog! We had a basement that had plaster walls which was a cheap way to finish a basement back in the 70s, but it turns out to be a nice warm yet reflective ambient space if the walls are made of that. So we put the drums in the basement with a concrete floor with plaster walls and then when it was time to do the vocal, we did them in the living room where there was a bit of a taller ceiling. It was a sunken living room. My mother was an interior decorator and she wanted to have this living room that was low. It was almost like I guess you would call it a small parlour in England. And there was a fireplace there and we cleaned everything out so that the ambient space of the room would warm the vocals up in a positive way. So we were using every little advantage of our location and environment. At the same time it was a transitional time in recording science. There were a few home studio options that had only recently become available for multi tracking digitally. Tape machines in particular that were efficient but not long for this world. It was sort of the period from ‘96 through to 2003 when this generation of poorly made but very functional, I would call them ‘pro-sumer’ units, were introduced that you could make a record on and if you were quick enough you could get the quality sound off of those onto a tape, and you’d have done the job. You kind of trick yourself into doing something professional. So we had all these new gadgets and we saved up and only spent our record company advance, which was $50,000, on the most efficiently professional tube gear that were on the market. There were a few units from Manley which was a newer company back then and I remember that I bought a knockoff of Rupert Neve preamp. There were a few other things that we bought just one at a time so that we could have that particular professional sheen on some stuff. But we were not in any way professionals. In fact, I would say at that point we were semi-advanced to amateur, right? So we barely made the grade. The mixing job that David Sonar did on the record down in Nashville was what put it over the top in terms of it actually sounded like it belonged in certain places. The reason I picked him is because I saw one of his credits was the AC/DC record For Those About To Rock. Now AC/DC for me has always been a lo-fi band that punched through into the bigger spaces and carried with them all of the charm and dust from the basement and the garage into that bigger space. So I wanted that sensibility, and they really nailed it on Teenage Dirtbag in particular, and on the other songs I think he did a fine job. So we got a very, very lucky with a little bit of skill and gear that we had acquired and with the space that they wound up in, just enough to make it sound like you’d think it’s a real record.

Teenage Dirtbag: A Cultural Anthem of the 2000s

The songs that would emerge and make the cut for the album showed a band that was hugely socially aware and that was perhaps on a mission to call out the realities, the injustices and the stuff that society was generally tolerating. Straight off the bat, songs like Truffles just don’t hold back in their messaging, and Hump ‘Em N’ Dump ‘Em where, for me, it’s about telling people to take responsibility and not blame things on others. From a lyrical perspective there were some harsh lyrics. I think the point I want to make is that this was quite a risk for the band to take in terms of public acceptance. To what extent were you placing the importance of the songs and what you wanted to say over commercial success?

Well, I have to say, and I hate to remind everybody, but the name of this song is Dirtbag. They wanted me to put on a silk shirt or new pants or something and I had to remind them: “You’re upset that I’m a little unkempt, guess where I came from!?”. That’s not who I am, Truffles is a litany of the horrible shit that kids in my boys school used to say to each other on a daily basis right before they’d get into a fist fight. Love Is A Mutt From Hell is a genuine story and basically a transcription of conversations I had two friends who were in their first sort of adult live-in relationships. They were falling apart and they were becoming disillusioned with the idea of having a family at all. Hump ‘Em and Dump ‘Em is a story about what if Clarke Kent’s landlord didn’t care that he’d saved the planet and only wanted his rent from him? The way that the 1996 Media Consolidation Bill had been written by the Democrats, there was a bit of a betrayal of a new deal spearheaded by Bill Clinton and Phil Gramm, right up to the point that they repealed the Glass-Steagall Act and put everybody’s house on the Wall Street gambling table. So there was this abandonment. Suddenly, as we were coming of age Generation X people, as we were beginning to enter our mid to late 20s, the time when our parents were settling into their first home purchases and establishing families, we were coming to the realisation that we were the prey, that we were going to become indentured servants to credit card companies, and that the debt they were looking to saddle us with was going to be permanent, and that the old rules didn’t apply where there were these protections built into the system where you couldn’t be swindled and scammed. We knew it was coming and we new that the next generation was fucked. It felt to me like I’d had enough of everybody’s bullshit at the end of the 90s and I was just ready to say it because we weren’t going to have anything to lose anyway! So what’s the sense of not saying exactly what happened? In fact, if anything, the album is cleaned up a little bit. Punk Ass Bitch wasn’t a song that I wrote. That was our bass player Rich Liegey. We had a deal back then that if you brought a song to the table you told everybody what they were supposed to do on it. You are the captain of the song so to speak. And when I asked him what he wanted me to do, if he’d have said “just said stand on your head and play a kazoo” I would have done it. But instead, he said “I want you to go home”! (Laughs!). So I went home and had a day off and got some extra sleep, and then came back a-day-and-a-half later and sang the final cut of Teenage Dirtbag. That was part of the compromise of being in a band with people. Obviously, my relationship with Rich didn’t last very long after that but that was what we were doing, and all these years later people still want to hear some version of that song whether that be the Jackie Chan cut or the original - and we do play it. So referring to your bigger question, yeah, it’s a dirty, snarling, foul mouth, sarcastic - almost nihilistic in some sense - snapshot of what it’s like to realise that you’re not going to get the same chance your parents got in a broad sense. It’s a quality of life acceptance record, you know?

Absolutely! And when I think about Sunshine which was the first song that was written for the album, you’ve said in the past that it came from realising that you were working for the wrong kind of people. It seem to have been a catalyst for the most wonderful protest. Was this intentional?

No, but what you’re speaking about, if you experience it that way, it’s a by-product of the person that I was at the time. I have to tell you, we didn’t give a fuck. I had been through a lot of projects, I’d had a record deal come through on another project that I got cut out of which was a million dollar deal and I saw nothing from it basically. I wasn’t just cynical, I was actively seeking revenge (laughs!). I was angry and I was kind of like feeling a little nihilistic. At the same time that there was this excitement of like ‘Well, what can they do to us? Like, not put the record out? Fuck that, we’ll do it ourselves!’. This was 1999/2000 and within the next four years we could’ve made our own record label and put it out on YouTube. And I had seen the major-label system that I started the 90s sort of naïvely trying to be a part of and I had seen that system change and start eating itself with these $25 CDs that had one song on it, right? That was a thing in 1999, that’s how much CDs cost: $29 or $30. It was insane! And I just thought ‘Nah, man!’, like if they only focus on 1 song, what are you gonna do? You’re going to convince them to make you a career legacy act? They don’t even see that far anymore so don’t even bother trying to get their attention on that shit because they can’t do it. Anyone at the label who used to be able to do that, they retired in 1987, you know? What I mean is being able to cultivate and bring up a band with their first three records, the way that REM had and Aerosmith had, where they are developed. There was this sense of ‘you’re on your own, kid’. Even if you get this big record deal with Columbia records which is one my favourite legacy labels because of Willie Nelson and Bruce Springsteen and all these wonderful acts, even knowing that I knew at the time that it was going to be over because they were going to start turning out these one song albums. And I thought, well maybe there’s a chance we get through the gate with one tune – because that’s all they ever do, stick to one tune and get obsessed with it – if their record has the genuine article, that being you just say what you want, then maybe in the long run it will be subversive, maybe. And I think Blink 182 has this kind of thing going for them as well because they even took the parody to the point of boy band videos. So they were playing the game with even more tongue-in-cheek than even we had the vision for and got through. And if you listen to those Blink 182 Records, there isn’t one song that’s subversive, there’s like 10 that are bald-faced, almost nihilistically acceptant of the fact that this generation is absolutely fucked. And what can you do about it? Longview by Green Day was very much ‘What am I going to do? I’m a target for credit card companies and bad student loans’. So it was kind of like that time where it was like ‘Oh boy, this isn’t going to end well’ and everybody kind of knew it and it wound up in the music. And in the way that you’re describing, that’s how it ended up in ours.

We’ll let’s talk more about Teenage Dirtbag because I remember when it came out and it’s wonderful to hear you talk about how you had a vision for a sound that was multiple genres, because that’s what it was for me, just something completely new and fresh because it blended hip-hop beats with heavy metal guitars. In the past you’ve described the song as autobiographical and I think one of the reasons so many people connected to that song is because you were writing their story too. And I just wanted to talk a bit more about how that song has changed people’s lives and the impact it’s had, and I don’t think there’s any better example than the story shared by Ed Sheeran. In July this Year, you performed with Ed at the stadium show in Hamburg in Germany. As part of the intro Ed shared how at 12 years old he used to perform Teenage Dirtbag with his teenage band and overall how that song was so incredibly important to him, and he would go on to be one of the biggest stars in the world. But regardless of where he ended up, there are thousands of ‘young Ed Sheerans’ doing exactly the same thing. How did it make you feel when you heard Ed’s story?

I was really kind of emotional about it actually. When I was 10 years old, I didn’t have a bunch of friends like that who played music. I had maybe one and his dad didn’t like it when you hung out at his house. I saw Angus Young on TV in a video and I was so obsessed! I was absolutely stunned by how great this guy was to watch and to listen to. And I did think to myself at the time ‘I don’t know how it’s done, I have no idea’ – and I barely even played guitar at the time – ‘but if I can do any version of that in my life however small, and if it’s sustainable and it puts food in my mouth, I’m doing it! Any level of that, I’ll take it!’. Ed has this group of friends who are still jumping on stage with him all these years later from his grammar school days. There is something from me watching Angus Young in 1983 or whatever that is still some part of the glue that holds his friends together and some indirect way. And it’s such a remarkable energy source that music can be because you can make something from nothing and you can go and do these unpredictable, weird connective tissue events. It could seem like magic if you think about it that way because all it is is like this daydream, this 10-year-old daydream. That’s all it is! If it’s mine in 1983 watching Angus, if it’s Ed’s with his friends playing Teenage Dirtbag, it’s just a kids daydream. It’s the connective tissue of human purpose in our case, and it’s not just our song but all of the collective energy of music and what you get from it when you’re experiencing that level. No I don’t get hit the way that Angus hit me when I was 10 years old – I don’t get hit like that with every piece of music. There’s got to be something about it. You watch Ed do a 3 hour concert virtually by himself, he’s raw doggin’ it, he’s got no click track or backing tracks - none of the safety nets of the pop concert industry are there to save him. He’s fucking doing it! He’s doing it AC/DC style. He doesn’t have to have the big crunchy guitars or any of that stuff but he’s doing his version of it with no net. When I found that out, I was just completely re-inspired with the notion of performing. So I had a little bit of extra juice when I stepped on stage with him that night because I had only the last 48 hours gotten a glimpse under his hood and seen how he does this stuff, and I thought ‘Holy shit, he’s actually the real thing!’. He went from this little garage band with his buddies to being this high wire artist in front of 63,000 people a night!

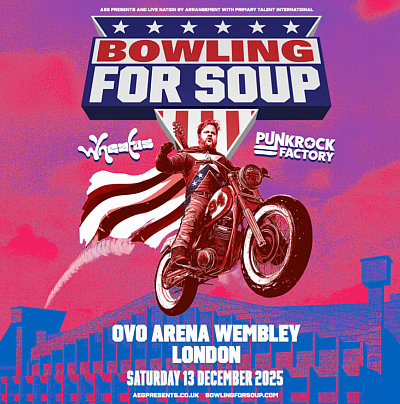

The wonderful thing is that Wheatus are hugely celebrating this 25th anniversary with lots of live shows including a forthcoming UK tour. Beginning in November, you will be playing a massive 18 shows with the final show being at Wembley Arena with your friends Bowling For Soup. The UK has a massive love for Wheatus – what does it mean to be coming back to the UK and for the climax to be a show at Wembley Arena?

We played Wembley one time opening for Busted and it was the first time in our modern lives back in 2016, and when I say ‘modern lives’ I mean like the ‘post the first decade’. At that time we had maybe 17 or 18,000 people singing back to us. That many people taking a song away from you, because that’s what happens with that song, they tell us in so many ways ‘this is our tune’. The fact that that can still happen after we made a conscious decision back in 2000 when we first started touring the world that we would choose smaller venues over large… A booking agent said to me “Do you want 9 shows in the big cities that last the better part of 2 weeks or do you want to stay there for five weeks and play 36 shows?” and I said “36!”. So we spent the last 25 years playing the Scunthorpes and the Loughboroughs and Newton Abbot! (Laughs!) Just so many places that bigger bands don’t typically go to. It’s great to play so much and not just go over there to do 9 shows where just about the time when you’re getting warmed up, you’re done. So we are glad for that decision and to occasionally get the big venue and have it all come together in a gigantic singalong because of all the time invested in the far-flung little spots, it makes the transition possible. So a lot of bands that play small places, they have a hard time getting into a bigger spot and filling it and making it seem intimate, but the intimate setting is all we’ve ever known and we don’t do anything different when we’re on a big stage. We might move around a little bit more because there’s more space. But as a songwriter, there is no songwriter who hasn’t dreamt of their song being in that environment, the 15 to 20,000 seat arenas. You certainly daydream that at some point and it can also kind of feel like a natural habitat for a big tune. We are super lucky that Teenage Dirtbag can fill both sockets. It’s so cool and fortunate for us that we can have the Ed Sheeran experience and then play King Tut’s Wah Wah (Laughs!) and just have a two hour ripping blast with everybody where the walls are sweating. We are the luckiest band in the world to be able to do both!

Our closing thoughts...

As Wheatus gear up for the next chapter, their reflections on the past 25 years reveal a band that’s never stopped evolving—creatively, emotionally, and sonically. Whether it’s the basement-born grit of their debut or the unexpected global embrace of Teenage Dirtbag, their story is one of resilience, reinvention, and staying true to the weird and wonderful heart of rock. And if the dirtbag spirit lives on, it’s because Wheatus never stopped believing in the power of a good song and a great story. To find out more, head over to www.wheatus.com and in the meantime, take another opportunity to enjoy the video for Teenage Dirtbag below.